Uniting the worlds of

scholarship and policy

Recent Commentary

Articles

James Borton

Turning Tides: Climate Change Watershed Prompts Reevaluation of Nuclear Energy and Deep-Sea Mining

James Borton

James Borton

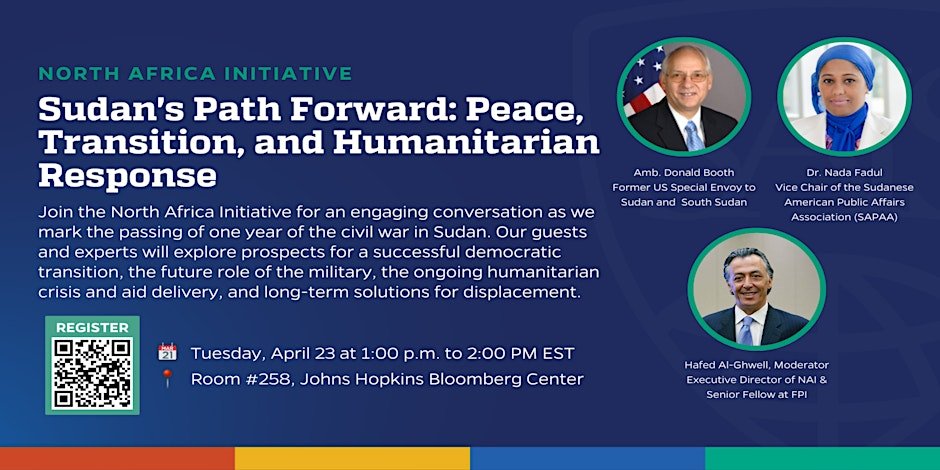

Upcoming events

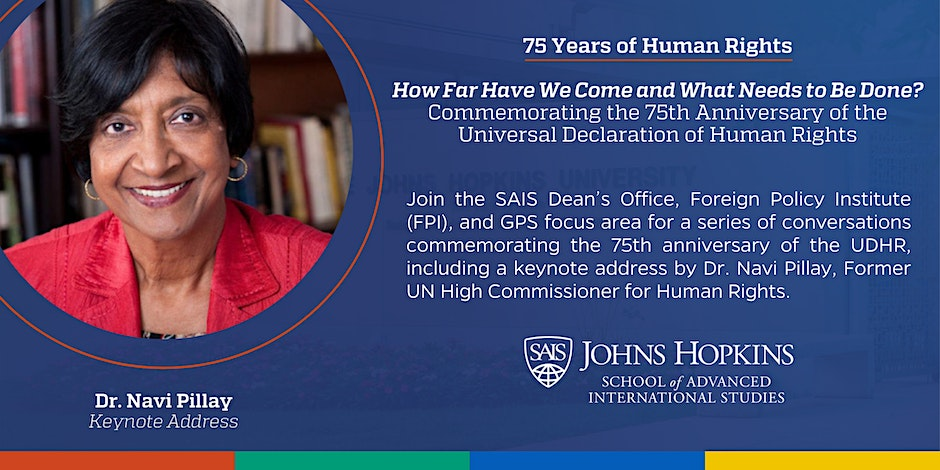

Past Events